It’s no secret that pollution is pretty bad for you. Thankfully, in most western countries nowadays pollution levels are pretty low. Here’s a neat little website that shows pollution levels all around the world. If you live in a westernized country, chances are you’re in the green with regard to pollution levels. But even if you weren’t, around 90% of time is spent indoors for most people anyways.

So no problem, right? Well, not exactly. Throughout the last several decades there’s been various changes in building designs to improve energy efficiency, mostly in the form of superinsulation and reduced fresh air exchange. In short, contemporary buildings are made much more airtight than older structures.

This isn’t necessarily bad as it drastically cut down energy costs. However, when combined with all the modern synthetic materials used in building materials, fabrics, paints, carpeting, cleaning products, fabrics, etc., a condition known as Sick Building Syndrome can occur. In short, poor ventilation and the outgassing of much of these products can cause residents to suffer from headaches, irritation, dizziness, etc. Indoor air pollutants are often at levels “2 to 5 times higher than typical outdoor concentrations.”

Indeed, indoor air can “contain over 900 chemicals, particles and biological materials with potential health effects.” It’s difficult to measure and quantify the risks of indoor air pollution since there is still insufficient data and the research is immature. Likewise, there is great variation in the levels and types of pollutants across different households.

Despite that, it doesn’t seem like it would hurt to look further into this. If there are simple ways to dramatically lower levels of indoor air pollution, then why not? Also, the EPA consider indoor air quality to be one of the top five environmental risks to public health, so it’s probably worth looking into.

My initial thoughts were to use plants. After all, plants are known to produce oxygen, purify the air, and we evolved all around them, so it sounds like a good thing to start with.

But which plants? Darn, if only an independent agency with a focus on scientific research performed a large-scale study on which plants were best for filtering the air of common toxic agents. Oh, thanks NASA. In 1989 NASA was looking for ways to clean air in space stations and tested a bunch of different plants and compiled a list of the best ones for removing compounds like formaldehyde, trichloroethylene, and benzene from the air. Some were especially promising like Peace lilies, Chrysanthemum, and Snake plants.

As a result, we start getting blog posts like this, this, this, and hundreds others disseminating NASA’s results and recommending the best potted plants for scrubbing your home’s indoor air. Some even mention how some of the tested plants “remove up to 90 percent of the toxins in your indoor air.” Alright then, problem solved. Pollution is bad for you and here are the best potted plants for lowering indoor pollution. Buy a couple of them and move on.

If only things were so simple. Let’s begin with dissecting the original NASA study.

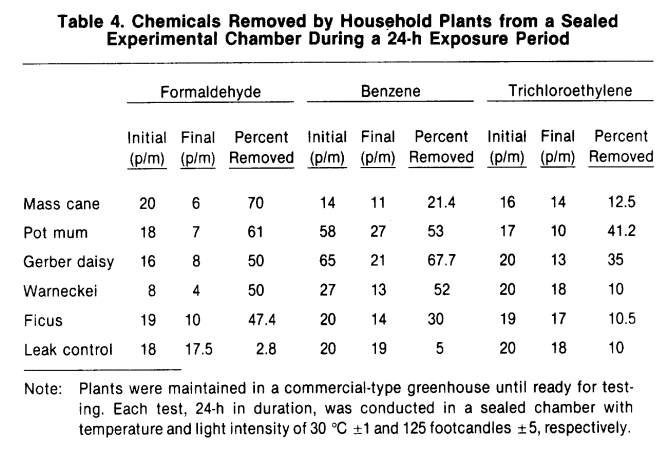

NASA designed small, sealed Plexiglas containers where they would seal a plant with an activated carbon soil filter for 24 hours. The experimenters injected a chemical such as formaldehyde or benzene into the chamber and collected air samples immediately, 6 hours later, and 24 hours later.

As for the results, they were quite variable. After 24 hours, depending on the plant and chemical, there could be anywhere between 10% and 90% removal. Here’s a screenshot of the relevant table, showing the most impressive six plants:

However, we must keep in mind several things:

- As previously mentioned, there are hundreds of chemical pollutants floating around, and this study tested just three. How well does this generalize to other toxins?

- NASA used charcoal filters that will provide for greater adsorption of toxins.

- The lab was testing with ideal conditions. The chambers were small (between 15 and 30 cubic feet) and single chemicals were injected once at the start.

- Imagine an average 150 square foot room with 8 foot ceilings. That would be 1,200 cubic feet, so you’d need around 75 small plants with carbon filters in that room to match NASA’s results. John Girman estimates around 680 plants would replicate the results of NASA’s chamber study in a 1,500 square foot home.

- Even then, the results wouldn’t match because homes have constant generation of chemicals such as formaldehyde via outgassing.

- Lastly, the NASA experiment used sealed chambers, whereas modern homes have ventilation and air exchange, further confounding the applicability.

As an aside, it was later shown that the primary contributors to the reduction of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were rhizosphere microbial activity of plants. That is, the microorganisms in the soil were doing the majority of the work and in some cases the foliage actually inhibited toxin reduction by forming a boundary layer on top of the soil.

Additionally, indoor air streams are fairly still. This study talks about the limitations of using potted plants and suggests ways of using biofiltration via actively exposing the air stream to the rhizosphere of plants. For significant air scrubbing, a method would need to be devised to provide efficient gas exchange between the soil and air. Measures would then need to be taken to prevent the drying out of the soil and the humidification of the ambient air.

Okay, so maybe the results won’t be as impressive as ideal laboratory conditions, but at least it’s something, right? Besides, look at all the benefits of plants:

- Common potted house plants are cheap, so it’s not a large investment.

- They’re mostly low-maintenance, with most requiring watering once a week or so.

- They’ll at least clean some air and make some oxygen.

- Everyone loves plants! They brighten up the room and are great decoration.

- There have been studies showing they can be therapeutic, lowering rates of depression and generally just increasing well-being and motivation.

So yeah, why not then? It’s low cost, and may very well be low benefit, but they’re probably still worth it, right?

Maybe. Let’s continue with reviewing the relevant research.

After NASA’s study people were curious of how the effects stack up in the real world, so similar experiments were performed, but this time in homes and offices.

Healthy Buildings International (HBI) designed an experiment in Arlington, Virginia where two identically furnished office floors would be run on separate but identical ventilation systems, with both floors sharing a common outside air intake. The ninth and eleventh floors were chosen, and both floors were asked to give up their plants for a month-long period where baseline measurements were taken. Following this, for the first four months the ninth floor was filled with many plants, and for the last four months, plants were present on both floors. Measurements of VOCs and airborne microbes of both floors were then taken over the duration of the experiment.

The results?

The authors concluded the “levels of VOCs on the ninth floor remained essentially the same as those on the eleventh floor throughout the duration of the study.” So there was practically no difference between the two floors.

Dingle et al. then tried their luck in 2000 in an Australian study where they found some office buildings and added five plants every other day to each room (to a maximum of 20 plants) in the experimental building. They used two adjacent buildings with no plants as controls. At the end of the study the authors concluded there was “no change in formaldehyde concentrations with the addition of 5 or 10 plants in the rooms and only an 11% reduction in formaldehyde concentrations with 20 plants in the room.”

So again, not much, and the paltry 11% may very well just be statistical noise.

Okay, well what about oxygen production? They may not be excellent scrubbers but at least they can help turn some carbon dioxide into oxygen, right? For example, the Snake Plant is recommended to put into your room at night because unlike most plants, it also gives off oxygen at night.

Unfortunately, the amounts are mostly negligible. Consider that air on average contains around 20.95% oxygen and 0.04% carbon dioxide. Even if you filled your home with plants and they converted all the carbon dioxide, the oxygen levels would only increase from 20.95% to 21%, which wouldn’t even be noticeable. Also, decomposing organic matters in many potted plants can cause a net increase in carbon dioxide.

Even if this wasn’t the case, animals and plants both engage in respiration, 24 hours a day. During the night when photosynthesis can’t take place, most plants continue to use oxygen while not releasing any back into the room. However, as previously mentioned, all these amounts are trivial.

Okay, maybe the scrubbing and oxygen generation potential are negligible, but it’s not like plants can do any harm, and they’re still good decoration.

To summarize, a team at the University of Georgia conducted a study to measure the amounts of VOCs released by common indoor plants (Peace Lily, Snake Plant, Weeping Fig, and Areca Palm). As it turns out, our friendly plants aren’t so innocent after all. They found on average 16 different VOCs released by these plants. The actors responsible?

- The plants themselves.

- Micro-organisms in the plant’s soil.

- The plastic pots containing the plants. Here’s some alternatives.

Additionally, people may be allergic to some plants, and other plants may affect the moisture content in the air, promoting mold growth. Plants may also be grown with fertilizers and pesticides that could have harmful effects on humans. And don’t forget about the possibility of bugs!

So, plants both input and output various VOCs in variable amounts. They may still be a net benefit, but as previously stated, the effects are likely negligible one way or the other.

Alright then, what about this? Some sites have been reporting it. Here’s the abstract:

New University of Technology Sydney (UTS) research made possible by nursery levy voluntary contribution funding has found strong evidence supporting the benefits of office plants for reducing stress and negative mood states in office workers. Plants were found to promote wellbeing, and therefore, potentially performance. Staff who had plants placed in their offices showed reductions in stress levels and negative feelings of a magnitude of 30 to 60%, while those with no plants recorded increases in stress and negativity of 20 to 40%, over the 3-month test period. Importantly, just one office plant was enough to make all the difference. In this Nursery Paper, the researchers involved outline their findings.

The study starts by talking about how significant amounts of studies have shown that potted plants have been effective in reducing VOCs emitted by plastics (furnishings, furniture, computers, etc.) and carbon dioxide in the air. Then, since clear air leads to clear thinking and better cardiovascular health, that perhaps potted plants could also reduce depression and stress and lead to better moods and improved worker performance and productivity.

The experimenters obtained a baseline measure of wellness via a Lifestyle Appraisal Questionnaire. The questionnaire confirmed the staff had physical and mental scores similar to those in their general demographic. They then gave the workers some plants (between one and four, or none if you were in the control group).

They also had them complete other various psychological measure questionnaires: The Profile of Mood States (POMS) and The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). Most people are familiar with surveys like these-they ask you a question and you respond with how you feel on a four/five-point scale. They then waited three months and had them take the questionnaires again.

Needless to say, they were thorough. Here are the results from the study in table form:

Extremely impressive! With the addition of just a few plants, the researchers were able to provide a significant (and statistically significant!) reduction across the board in all the negative psychological feelings being tested. If this indeed the case, the addition of plants to office environments may very well be the single most cost-effective measures businesses can take to improve worker morale and productivity. The study’s conclusion: “This study shows that just one plant per work space can provide a very large lift to staff spirits, and so promote wellbeing and performance”.

However, I’m a bit skeptical. Here’s why:

- The placebo effect. If you need any reminding in how powerful it can be, here’s some light reading on the matter. If you take a wellness questionnaire and then you and the entire office immediately receives some plants, you may soon suspect that these plants will be improving the tested feelings, which will then improve those feelings.

- The addition of plants may show that your employers care about you because they are giving you free plants to try and improve your well-being. Who doesn’t love plants? This may cause you to like your job and superiors more.

- The existence of the experiment may have caused behavioral changes in the staff working there.

- Sick building syndrome can often dissipate over time as outgassing is abated or people just plain get used to it.

- Similarly, over time people can get used to the office environment and have lower levels of daily stress from being familiar with their role and coworkers.

- This could have coincided with other health interventions. For example, upon being questioned about their psychological health or upon the addition of potted plants, workers may become more cognizant of their mental health and do more to improve it both in and out of the office.

- The control group is all over the place. A 32% reduction in depression coinciding with a 42% increase in negativity? What gives? The study comes out and says that the control group had a small sample size (9 people..) and thus is not statistically significant.

- This basically puts the entirety of the study into question. Had the control group been of similar size to the experimental group, we may have very well gotten identical results in both. Now we don’t even know if the plants did anything!

- Could they do it again? Remember everyone, if you ever need any more reasons to doubt a study’s results, just mention the replication crisis and publication bias!

So, the study results may very well be bupkis. Or maybe not. Who knows?

Anyways, time for the conclusion. My thoughts on the matter are probably the following: unless you live in a nursery, the effects from plants on pollution and oxygen levels in the air are mostly negligible. On the other hand, I wouldn’t be surprised if the placebo effect from plants is strong enough to provide significant effects on physical and psychological health. If that’s the case, oops, reading this article may have harmed your health, but probably not by much.

Lastly, if you actually want to improve air quality significantly, the most practical advice may be to just open some windows or buy some heavy industrial air exchangers with fancy filters.